Introduction

If we carry on with business as usual, tearing down forests, expanding animal agriculture and increasing the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, we can expect more of the following1https://www.ekoenergy.org/extras/climate-change/:

- Many plants and animals will become extinct

- The loss of wildlife will increase, threatening important ecosystems and ultimately our survival

- Ocean acidification will destroy marine life

- Glaciers and sea ice will melt

- Sea levels will rise

- Coastal cities will flood

- Places that currently get lots of rain and snowfall will get hotter and drier

- Lakes and rivers will dry up

- Droughts will make it hard to grow crops

- There will be water shortages

- Less predictable seasons will threaten food security

- Hurricanes, tornadoes and storms will become more common

- Certain diseases will increase, eg malaria and dengue fever

- The likelihood of conflict will increase

Extreme weather

As a result of climate change, we are now seeing extreme weather events more frequently around the world.

This is the case in Uganda with events particularly increasing over the last 30 years, and in 2019 it was the fourth most-affected country by extreme weather.2https://www.fes.de/en/shaping-a-just-world/article-in-shaping-a-just-world/ugandas-silence-at-cop26-over-growing-deforestation Erratic rainfall has caused rivers to burst, mudslides and landslides, especially in mountainous areas. Floods have devastated towns and villages in the lowlands. The country is also experiencing prolonged dry seasons leading to loss of crops and livestock. Many lives have been lost and millions of people affected with livelihoods and properties ruined in these extreme weather events.3https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/uganda/vulnerability

During the summer of 2022, intense heatwaves covered large swathes of Europe, China and North America. Temperature records were broken in the UK, Italy, France, Switzerland, Germany, Poland, Hungary and Slovenia and there were 24,000 heat-related deaths in Europe alone. Climate change made the record drought across the northern hemisphere at least 20 times more likely. Without it, they say, such an event would happen only once every 400 years.4https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/without-human-caused-climate-changetemperatures-of-40c-in-the-uk-would-have-been-extremely-unlikely/

In August 2022, the Government of Pakistan also declared a national emergency but for a very different reason. Unprecedented rainfall from mid-June until the end of August left a third of the country under water. The rains and flooding affected over 33 million people, destroyed 1.7 million homes and nearly 1,500 people died. Climate change could have increased the most intense rainfall over a short period in the worst affected areas by 50 per cent.5https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/wpcontent/uploads/Pakistan-floods-scientific-report.pdf

These are just a few examples from around the world and there will be more to come. Forty per cent of the world’s population, a staggering 3.5 billion people – including the population of Uganda – are highly vulnerable to climate impacts.6IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp. It sounds as terrifying as a science fiction disaster movie but it’s not unrealistic. And it is not just mass extinctions and extreme weather events we need to be concerned about (as if that wasn’t bad enough), but also political unrest, mass migrations and conflict. Future wars being fought over water are becoming a real possibility. The future of the planet is at stake and urgent action is needed now.

Global heating

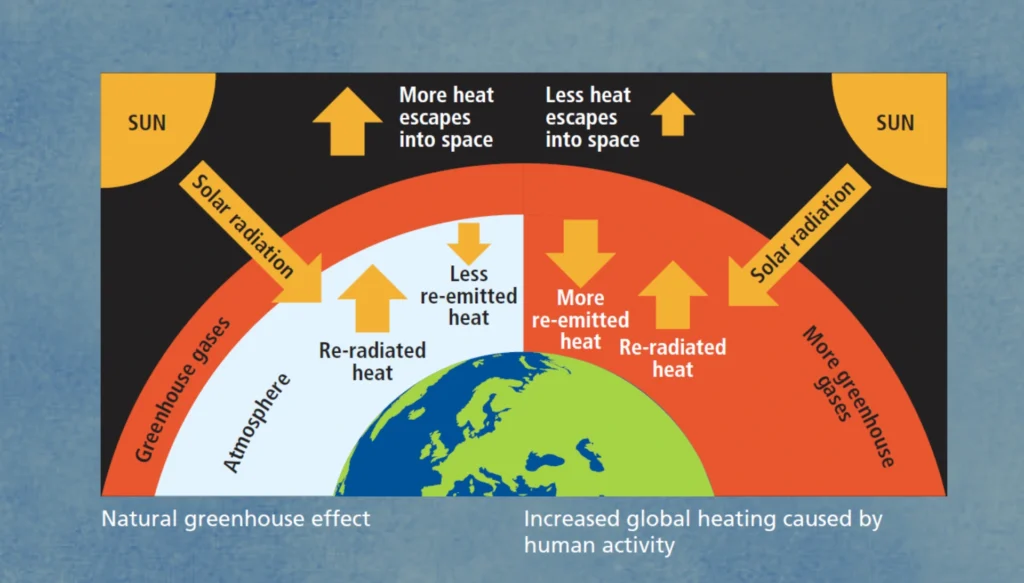

As shown in the diagram below and in this short video by NASA, the Earth is surrounded by a layer of gases we call the atmosphere. It forms a protective layer. In the daytime the sun shines through the atmosphere warming the Earth’s surface. At night, the earth’s surface cools and releases heat back into the air. But some of that heat is trapped by the gases in the atmosphere; these heat-trapping gases are called greenhouse gases. Carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are examples of greenhouse gases.

Earth needs just the right amount of gases in the atmosphere to keep the temperature within the correct range for life to exist. But some human activities – such as livestock farming, destruction of forests and burning coal and oil – are changing this natural greenhouse effect and increasing greenhouse gases, causing the Earth to warm up too much.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is the most abundant greenhouse gas and is now 50 per cent higher than in 1750 – the beginning of industrial times.7https://www.carbonbrief.org/met-office-atmospheric-co2-now-hitting-50-higher-than-pre-industrial-levels/ Other gases, such as methane and nitrous oxide, are emitted in smaller quantities but trap heat more effectively and can be many times stronger.

How farming animals contributes to the climate crisis

Farming animals contributes a massive 20 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions! (This includes growing crops to feed to livestock.)8Xu X, Sharma P, Shu S et al. 2021. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nature Food. 2, 724-732.

Find out more

In 2006, the United Nations’ report Livestock’s Long Shadow estimated that livestock farming accounted for 18 per cent of man-made greenhouse gas emissions – a bit lower but still more than all the world’s transport – cars, buses, trucks, trains, ships and planes – combined.9www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM In 2013, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations revised the figure to 14.5 per cent.10http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf However, scientists say this estimate was based on outdated data, and livestock emissions, especially methane, are likely to be much higher because breeding and feeding methods have changed.11www.biomedcentral.com/about/press-centre/science-pressreleases/29-09-17 12Twine R. 2021. Emissions from animal agriculture – 16.5% Is the new minimum figure. Sustainability. 13, 6276. The meat industry likes to distort statistics in their favour and talks about livestock’s ‘direct’ emissions being closer to 10 per cent (rather than 20 per cent), ignoring land use changes such as deforestation. This is an unacceptable deception.

The leading causes of deforestation are:

- using more land for grazing cattle for beef

- using more land to grow soya – to feed poultry, pigs and other livestock including farmed fish

Around 80 per cent of global soya is used for animal feed, while just seven per cent of it is used for foods for direct human consumption, such as tofu and soya milk. In many countries, the vast majority of farmed animals are raised in factory farms and fed animal feed crops, such as soya, rather than roaming around fields munching grass all day. It’s not a pretty picture, it involves extreme cruelty and the environmental impacts are devastating.

Methane (CH4)

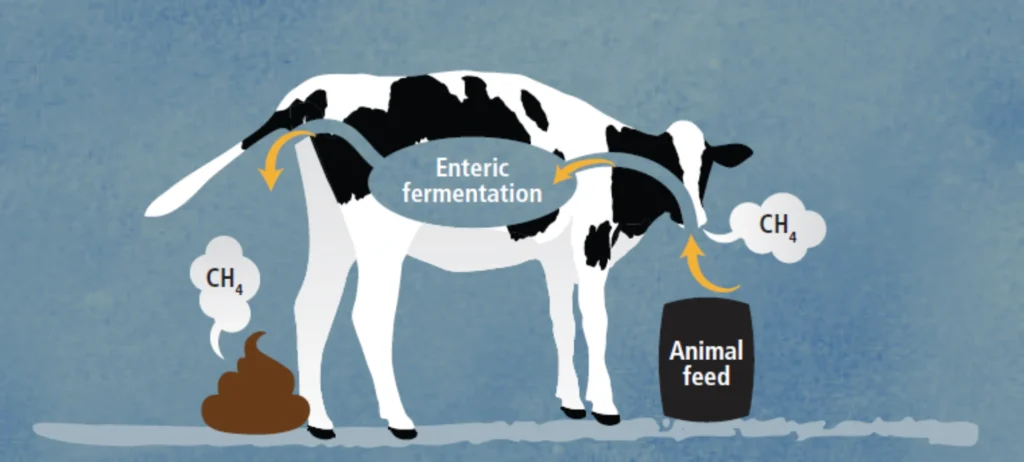

Livestock farming is the main source of the powerful greenhouse gas methane, with large amounts coming from cows, sheep, goats, deer and antelope. These animals are called ruminants – hoofed herbivores who graze to get nutrients from plant foods by fermenting them in a special stomach with four compartments that helps them break down tough plant matter. This process is called ‘enteric fermentation’ and it produces large amounts of methane gas which exit the animal – mostly in their burps rather than their farts.

Methane can have a big effect on the climate because it has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere. Concentrations in the atmosphere have more than doubled since the industrial revolution13IPCC. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2391 pp. and scientific research estimates that one quarter of today’s warming is driven by methane from human activities14https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/united-kingdom-methanememorandum/united-kingdom-methane-memorandum, making it a gas we need to keep an eye on and to reduce now!

Lowering methane emissions is one of the most effective ways to rapidly reduce warming and could really help global efforts to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. If methane emissions were cut by 45 per cent by 2030 this could avoid nearly 0.3°C of global heating by the 2040s. It would also, each year, prevent 255,000 premature deaths, 775,000 asthma-related hospital visits, 73 billion hours of lost labour from extreme heat and 26 million tonnes of crop losses across the world.15https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-methane-assessment-benefitsand-costs-mitigating-methane-emissions

Carbon dioxide (CO2)

Trees are an important carbon sink – meaning that they take carbon from the atmosphere and store it overground in their trunks and branches and underground in their roots. When trees are cut down and burned to make way for livestock grazing or growing crops for animal feed, carbon is released from the trashed trees and carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere increase.

It gets worse. The damage grazing animals cause to deforested land results in soil erosion, which releases more carbon and can lead to flooding.

Nitrous oxide (N2O)

Nitrous oxide is commonly known as laughing gas but is almost 300 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at heating the atmosphere, which is not so funny! Agriculture is also the main contributor of this greenhouse gas, mainly from nitrogen fertilisers.

Large amounts of fertilisers are used in crop production and as over a third of the world’s cereal crop is fed to farmed animals, it follows that livestock farming is a huge and unnecessary source of this potent gas.

The beef with beef

Meat and dairy are an inefficient and wasteful use of precious resources. Beef is one of the most wasteful and damaging industries globally, producing 40 to 60 per cent of livestock farming’s emissions.10http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf 16https://www.fao.org/gleam/dashboard-old/en/ It’s responsible for vast losses of carbon sinks – they cause carbon to be released into the air by damaging the soil and by farmers destroying trees to graze cattle, or to grow crops to feed them.

Cattle destroy native vegetation, their hard hooves damage soils and stream banks, and their poo contaminates streams, rivers and lakes. All these things lead to severe loss of wildlife and pollution. Growing vast amounts of crops to feed the cattle, causes excessive water wastage.

Much of the food cows eat is used just to stay alive. This is why it takes around 100 times as much land to produce a calorie of beef than it does to produce a calorie of plant-based alternatives. The same is true for protein – it takes almost 100 times as much land to produce a gram of protein from beef compared to protein from beans.17Poore J and Nemecek T. 2018. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 360 (6392) 987-992.

While methane is a significant contributor, it is not the only reason for the large emissions of beef and dairy. Livestock grazing and the production of animal feed crops are the main cause of global deforestation and land use change – huge contributors of greenhouse gases. Other sources include the large use of fertilisers to grow fodder crops to feed the cattle, nitrous oxide from manure, energy used by machinery, equipment and transport of cows to slaughter, plus food waste, which can be high for meat. Even if you discount methane entirely, foods produced from ruminants still have a high carbon footprint; the average footprint of beef, excluding methane, is still 10 to 100 times the footprint of most plant-based foods.17Poore J and Nemecek T. 2018. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 360 (6392) 987-992.

But people can’t eat grass so why not use land we can’t grow wheat or potatoes on, for example, for grazing? The idea that marginal land, with low agricultural value, can’t be used for anything other than grazing animals is simply wrong. Hardy human-edible plants, such as leafy greens, roots, buckwheat, rye, barley, quinoa and legumes (beans and other pulses) can all grow in a wide variety of conditions. In fact, growing plants improves soil health! Furthermore, some fruit and nut trees could also be grown on rough and marginal lands to supplement these vegetable and cereal crops.

A large-scale shift to a diet centred on plants, instead of meat and dairy, would reduce the total amount of land we use for agriculture by a whopping 75 per cent – an area the size of the whole of Africa! This vegan shift would free up all grazing land with huge benefits for wildlife and carbon storage – as well as providing the opportunity for growing more plant foods.

Other land could go back to rough grasslands, supporting multiple grasses, wildflower species and the wild animals that occupy these habitats. There would be an overall massive reduction in land use and we would be able to produce enough food to feed everyone in the world a nutritious diet. But this would only be possible with a widespread shift towards a vegan diet.

Dairy disaster

Dairy produces around 20 per cent of livestock’s emissions – more than pig meat, poultry and eggs combined.10http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf In the EU, dairy produces more emissions than beef.18Lesschen JP, van den Berg M, Westhoek HJ et al. 2011. Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 166-167, 16-28. Globally, the dairy industry produces four per cent of greenhouse gas emissions.19www.fao.org/3/k7930e/k7930e00.pdf This is a significant amount – especially when you consider that over 70 per cent of the world’s population is lactose intolerant and doesn’t consume any dairy!

The carbon footprint of food

The carbon footprint of food is a measure of all the greenhouse gases relating to the production of that food or meal. So, it includes growing, farming, processing, transporting, storing, cooking and disposing of food.

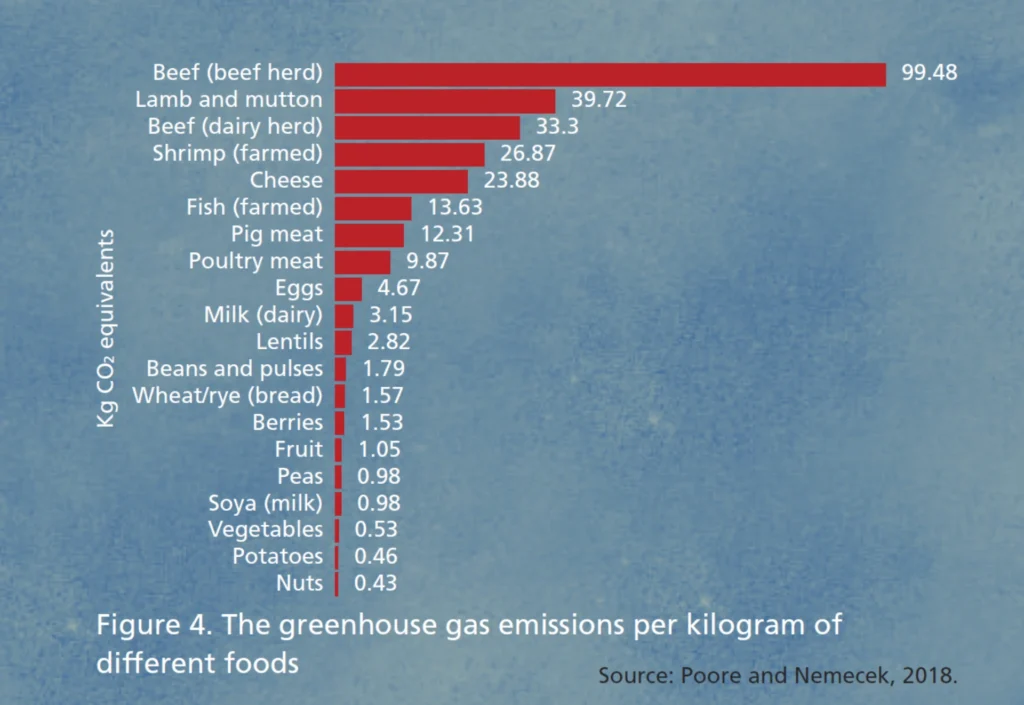

The carbon footprint of meat, fish, dairy and eggs is considerably higher than that of virtually all plant foods – with beef topping the list.

In 2018, the most detailed analysis to date of the damage that farming animals does to the planet was published in the journal Science. In the landmark study involving almost 40,000 farms in 119 countries, the environmental impacts of 40 food products that represent 90 per cent of all that is eaten were assessed. It looked at impacts from farm to fork, on land use, climate change emissions, freshwater use, water pollution and air pollution. It compared beef with peas, for example, and found that producing one kilogram of beef emits almost 100 kilograms of greenhouse gases, whereas one kilogram of peas emits just one kilogram of gases.17Poore J and Nemecek T. 2018. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 360 (6392) 987-992.

Another study compared beef to soya and found that one kilogram of beef creates the same amount of emissions as driving 100 miles in a car, while soya produces the same as driving just three miles.20Carlsson-Kanyama A and González AD. 2009. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5) 1704S-1709S.

If you look at the emissions from different food products in the diagram below, you will see how beef tops the table followed by other animal products, with plant-based foods producing the least.

Dairy versus plant-based milk

Cow’s milk and dairy products are a staple in many people’s diets but make a substantial contribution to the greenhouse gas emissions of food. In typical European diets, dairy accounts for over a quarter of the carbon footprint, sometimes exceeding a third.21Sandström V, Valin H, Krisztin T et al. 2018. The role of trade in the greenhouse gas footprints of EU diets. Global Food Security. 19, 48-55. In Europe, dairy contributes to about nine per cent of a person’s daily calories, whereas in Uganda it makes up about three per cent – and rising – of daily calories.22https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919223001604

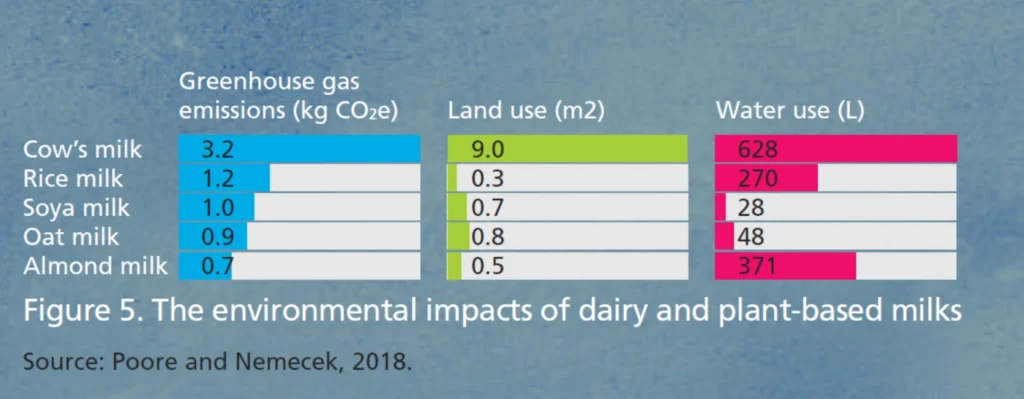

Dairy alternatives have now become a mainstream choice in many parts of the world, and the market for them in Uganda is also growing.23https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/dairy-products-eggs/milk-substitutes/uganda This is good news for the planet as all plant milks (eg soya, rice and oat), have a much lower environmental impact than dairy.

The diagram below shows how, in all aspects, cow’s milk has significantly higher environmental impacts than plant-based milks. Cow’s milk produces around three times more greenhouse gas emissions, uses around 10 times as much land and two to 20 times as much freshwater. If you want to reduce the environmental impacts of your diet, switching to plant-based milk is a great place to start.

If the world is to meet its climate targets and strive for the optimistic target of 1.5°C, big dietary changes will be necessary. While farming practises can be improved to become more environmentally friendly, they would still not have the same impact as a global transition to a vegan diet.24Eisen MB and Brown PO. 2022. Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO₂emissions this century. PLoS Climate. 1 (2) e0000010. A vegan diet could halve your food emissions.25Scarborough P, Appleby PN, Mizdrak A, Briggs AD, Travis RC, Bradbury KE and Key TJ. 2014. Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Climate Change. 125 (2) 179-192.

The 1.5 degree target – what does it mean?

It means that by the year 2100, the world’s average surface temperature will have risen no more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. The 1.5C threshold was the stretch target established in an international agreement of 195 countries, called the Paris Agreement in 2015. The agreement aims to limit global warming to “well below” 2C by the end of the century, and “pursue efforts” to keep warming within the safer limit of 1.5C. Find out more here.

References

References

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp.

- 7

- 8Xu X, Sharma P, Shu S et al. 2021. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nature Food. 2, 724-732.

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12Twine R. 2021. Emissions from animal agriculture – 16.5% Is the new minimum figure. Sustainability. 13, 6276.

- 13IPCC. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2391 pp.

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17Poore J and Nemecek T. 2018. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 360 (6392) 987-992.

- 18Lesschen JP, van den Berg M, Westhoek HJ et al. 2011. Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 166-167, 16-28.

- 19

- 20Carlsson-Kanyama A and González AD. 2009. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5) 1704S-1709S.

- 21Sandström V, Valin H, Krisztin T et al. 2018. The role of trade in the greenhouse gas footprints of EU diets. Global Food Security. 19, 48-55.

- 22

- 23

- 24Eisen MB and Brown PO. 2022. Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO₂emissions this century. PLoS Climate. 1 (2) e0000010.

- 25Scarborough P, Appleby PN, Mizdrak A, Briggs AD, Travis RC, Bradbury KE and Key TJ. 2014. Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Climate Change. 125 (2) 179-192.